As every child knows, it’s awesome when your parents let you eat ice cream, but not so much when they make you eat things like brussels sprouts, liver, or in Japan, that gawd-awful substance known as natto. For those of you who have never had the “pleasure,” count your blessings. If you can get past the stinky-shoe odor or the slimy over-cooked ocra texture, the strings of goo that will cover your face will leave you with a particularly “wonderful” reminder for the rest of the day, especially, if like me, you have a beard. (So, of course, my sons LOVE the stuff and always try to kiss me after a big heaping bowlful. I love them, but not that much.)

What most children don’t know, however, is that make and let are also known as causative verbs. How we allow our children to enter the first grade without this knowledge is a mystery to me.

And what any student who has made it to at least the intermediate level of English knows is that causative verbs are a major pain in the okole. (That’s the Hawaiian word for the part of your body that you sit on.) And they aren’t much easier in other languages either. I’ve been studying/speaking Japanese for over twenty years and I still can’t use the causative ~saseru properly. Don’t get me started on the causative passive ~saserareru.

However, like anything else, with practice, causative verbs don’t have to be the nightmare they seem to be for most students. All you really need to know to master causative verbs is how to use them (their patterns), when to use them (especially choosing the right one for the situation), and maybe most importantly, when NOT to use them.

Infinitives

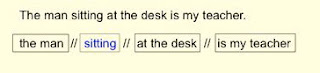

The first key to understanding causative verbs is an understanding of infinitives. By the time they begin learning causatives, all students should know what a basic infinitive is. An infinitive is simply to plus the base form of a verb.

- to sing

- to run

- to jump

- to scream in frustration when you study English

However, what many students don’t know is that there is a second kind of infinitive: the bare infinitive. Just like bare feet means without shoes, a bare infinitive is an infinitive without “to”. In other words, a bare infinitive is the same as the base form of a verb. The difference is, you NEVER add ~s to a bare infinitive the way you would a regular verb that follows he, she or it or add ~ed in the past tense. Bare infinitives never change.

The Most Common Causative Verbs: Make and Let

The two most common causative verbs are the ones used in the example above, make and let. Grammatically they are the same and both are very informal and conversational, but their meanings are completely opposite.

Make and let both use the same basic patterns.

- make / let someone do something

- make / let something happen

In a causative sentence, you always need two verbs. The causative verb is the main verb of the clause. The second verb, usually an action verb, is always a bare infinitive form.

- I made my brother hit himself.

- Sometimes, I let my son win.

In these examples, the first noun (the subject I) is the person who controls the situation. The second noun (the objects brother and son) are the people who will do the action, the hitting and the winning.

(I loved making my brother hit himself when we were kids. I could usually get in three or four shots before his screaming brought our parents running. Unfortunately, he got much bigger and stronger in high school, so I can’t do it anymore.)

To summarize, make and let are the same grammatically. They both use the same patterns with bare infinitives and they are both informal and conversational.

Their differences, on the other hand, are much more important.

If someone lets you do something, you are happy. It is something you want to do. However, you must get permission from someone, like your parents, your boss or a teacher.

- Our teacher lets us use dictionaries on tests.

- My parents let me borrow their car on Saturday.

- My boss let me go home early today.

Two helping verbs that are very similar to let are can and may, which you use to ask for permission.

- “May we use our dictionaries on the test?”

- “Can I borrow your car on Saturday?”

- “May I go home early today?”

Conversely, if someone makes you do something, you are probably going to complain about it. You don’t want to do it. However, you have no choice because your parents, your teachers or your boss have control over the situation. They have authority. You can’t say no.

- My teacher makes us type everything.

- My parents make me do chores around the house.

- My boss made me work late every day this week.

Two helping verbs that are similar to make are must and have to, which you use to give orders.

- Teacher: “You must type all of your homework assignments.”

- Parents: “You have to do the dishes and clean your room.”

- Boss: “I’m sorry, but you must work late again tonight.

In other words: let = happy / make = unhappy.

Other Causative Verbs: Require and Allow

Two other common causative verbs share the same similarities and differences as make and let. They are require and allow.

Require and allow are more formal. They should be used in writing and professional discussions. Also, they have a different pattern. They both need the full infinitive with to.

- require/allow someone to do something

- require/allow something to happen

Allow, however, has the same meaning as let. It is used to give permission, which makes you happy.

- The school lets students wear shorts and slippers at school.

- The school allows students to wear shorts and slippers at school.

As you might guess, require has the same meaning as make, and is used to give orders, or things you have to do.

- Most Asian schools make their students wear uniforms.

- Most Asian schools require their students to wear uniforms.

In this case, I much prefer the second sentence. Make just seems too strong. Require makes it sound like it's a rule, but it's an accepted part of life.

Common Errors

The most common error is a simple one. Students will often use the full infinitive (with to) with make and let.

- My father made me to wash his car.

- My mother let me to have ice cream for dessert.

Asking why this is wrong is like asking why it’s wrong to steal. The only answer that matters is because it is. I’m sure there is some reason going back to the 1500s and farmers in northern England or Scotland (I’m making this up, of course), but it’s just not important. The only thing learners have to do is learn it, and to learn it, you must practice it. In other words, just do it. (Don’t you hate it when you ask your father why and he says “Because I’m your father.” Same principle, same frustration.)

The second most common error is a much bigger problem. It combines the ideas of permission and happiness. (Remember that let = happy, make = unhappy.) If you ask your wife if it is ok to go to Las Vegas with your friends and she says “yes,” then you are happy, right?

- My wife let me go to Las Vegas with my friends.

However, if she says “no,” then you are unhappy, right? Therefore, you need the causative verb make, right? But you still can’t go, so you need the negative not somewhere, right? So, it must go with the infinitive, right?

- My wife made me not to go to Las Vegas with my friends.

WRONG!!! The mistake is only thinking about happy and unhappy, which is a good rule of thumb. However, you also have to think about the other rule of thumb: let = permission and make = order. This situation is still all about permission. The problem is that my wife won’t give me permission. Therefore, regardless of yes or no, let is still the correct causative verb for this situation.

- My wife won’t let me go to Las Vegas with my friends.

- My wife wouldn’t let me go to Las Vegas with my friends.*

When Should You Use a Causative Verb

There is a simple guiding idea that I use when I write and I advise all of my students to keep in mind when they write: Remember the KISS principle - Keep It Simple, Stupid. It is best not to use a causative verb if you don’t have to. For example, the following sentences have basically the same meaning:

- I have to read this book for English class.

- My English teacher is making me read this book for English class.

Both of them mean I think the book is REALLY boring. The first sentence simply shows my opinion of the assignment. I would only use the causative verb make if it is important to say who is in charge, or who made the decision.

In other words, if who gave the order, if who gave permission is important, then use a causative verb. Otherwise, use a simple sentence with the helping verbs can, must, or have to.

Simple, right? We've only scratched the surface, ya'll.

(I really appreciate questions, comments and suggestions. Feel free to post them in the Commestions and Comments link below or join my Facebook group Mr. K's Grammar World.)

________________________________________________________________________

*The first sentence with will shows that the trip to Las Vegas that I REALLY want to go on is still in the future. The second sentence with would shows that the Las Vegas trip is over. My buddies went and had a great time.

(I really appreciate questions, comments and suggestions. Feel free to post them in the Comments section below. However, I don't often see them right away. Instead, you can use the Questions and Comments link below or join my Facebook group Mr. K's Grammar World.)

Useful Links

- Questions or Comments

- Causative Verbs Practice

- Mr. K's Grammar World (Website)

- Mr. K's Grammar World (Facebook)

- The Devil Made Me Do It: Causative Verbs (Part I)

- The Devil Made Me Do It: Causative Verbs (Part II - Other Causative Verbs)

- The Devil Made Me Do It: Causative Verbs (Part III - The Passive Voice)

- The Devil Made Me Do It: Causative Verbs (Part IV - Adjectives and Verbs)

- The Devil Made Me Do It: Causative Verbs (Part V - For the True Grammar Geek)